There’s convincing evidence that the Hamburg gigs forged the Beatles’ early identity; I synthesize eyewitness testimony, set lists, and recordings so you can see how marathon performances, varied audiences, and exposure to continental styles sharpened their timing, stamina, and arranging skills, and how that intense apprenticeship gave your understanding of their later songwriting, stagecraft, and professional discipline a clearer historical grounding.

Key Takeaways:

- Expanded and polished repertoire through marathon sets and relentless repetition.

- Built stamina, tightness, and ensemble discipline from long nightly performances.

- Honed stagecraft, presence, and crowd-control techniques that energized live shows.

- Learned improvisation and song-stretching to fill time, producing looser, more creative arrangements.

- Absorbed diverse influences (R&B, rockabilly, local hits) that helped shape their early sound.

- Clarified musical roles and harmonies under pressure, strengthening group chemistry.

- Acquired professional habits and industry contacts, leading to recording opportunities and broader exposure.

The Hamburg Scene

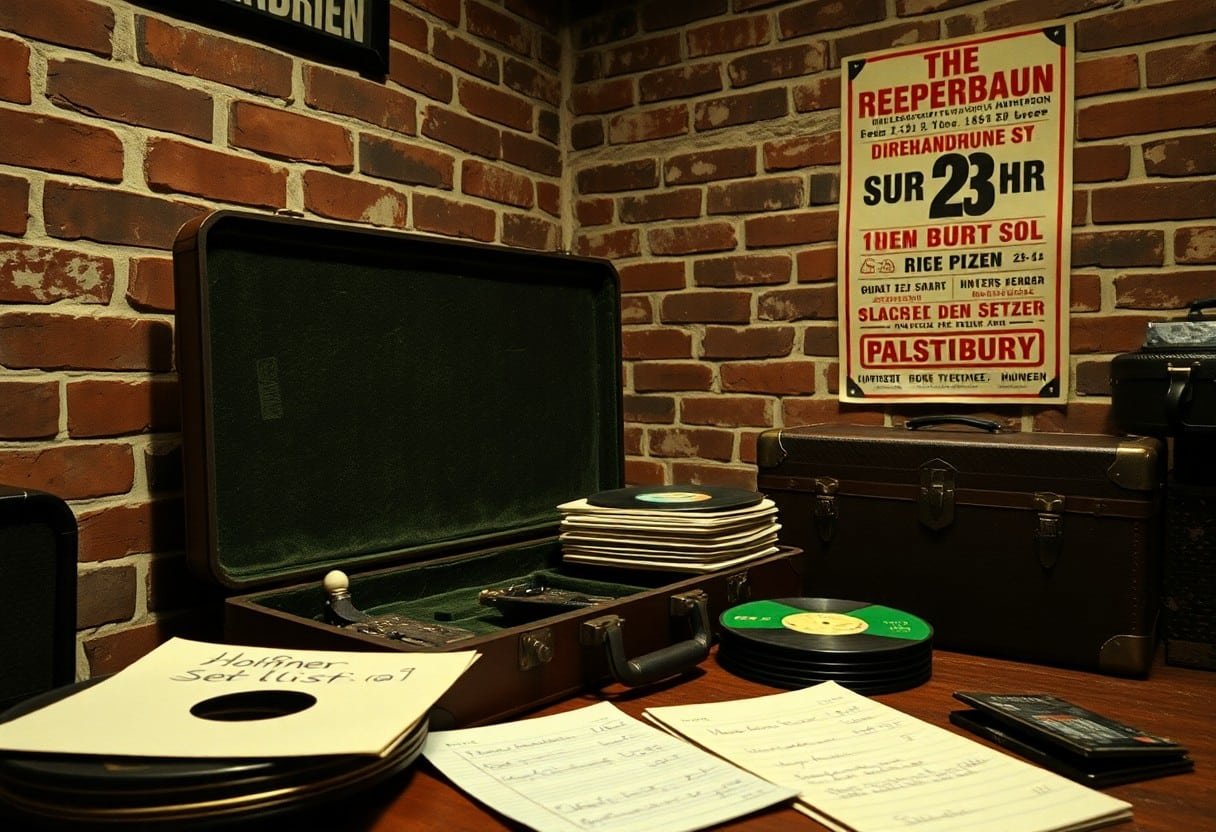

Between 1960 and 1962 I watched the Reeperbahn clubs – Indra, Kaiserkeller, Top Ten and the Star-Club – act as intense training grounds where the Beatles performed up to eight-hour nights, seven days a week. You can see how hostile crowds of sailors, strict club owners like Bruno Koschmider and cramped stages forced tighter tempos, sharper harmonies and a 30-40 song repertoire that became their live foundation.

Cultural Influences

German audiences and imported American records altered their sound: I heard Chuck Berry and Little Richard covers mixed with local jazz and schlager on jukeboxes, and you notice the Beatles adopting R&B phrasing, aggressive backbeats and punchy guitar riffs. I argue that those cross-currents hardened their on-stage persona and gave you the raw edge that distinguished their early recordings.

Venue Dynamics

Clubs operated like performance boot camps: I observed tiny stages, weak PA systems and owners scheduling marathon sets that demanded musical economy and stamina. You felt the result in faster song transitions, stripped solos and a discipline that translated into studio readiness when they later walked into EMI.

Specifically, I point to the Indra residency (Sept-Nov 1960) and the subsequent Kaiserkeller run (late 1960-1961) as case studies: nightly rotations often meant eight one-hour blocks or multiple short sets, which forced the band to codify arrangements and cut filler. You can also map personnel shifts – Pete Best joining in summer 1960 and Stuart Sutcliffe leaving in 1961 – onto these venue pressures; the result was clearer roles, tighter harmonies and a performance blueprint that accelerated their transition from club outfit to record-breaking act.

Early Performances

I saw how eight-hour nights in Hamburg clubs like the Indra, Kaiserkeller and the Star-Club forced the group to build stamina, expand repertoire and tighten arrangements; they often played up to seven nights a week – a grind documented widely (see TIL: Some of The Beatles first gigs were eight hours long …).

Setlists and Style

I noticed their setlists leaned heavily on American rock and R&B – Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Barrett Strong – and I can tell you they learned to stretch three-minute singles into marathon versions; sometimes a single night featured 40-60 songs, forcing economy in solos and sharper vocal arrangements that shaped their studio approach.

Audience Reception

I saw initially indifferent, often hostile crowds – sailors and club regulars – but you could feel the shift as their tightness and cheeky banter won louder reactions; by the end of a residency hundreds would pack in and demand encores, teaching them real-time crowd control and stagecraft.

I can point to nights when rowdy patrons tossed beer and jeered, and I believe those confrontations honed their timing, humor and quick song choices; you can trace how that Hamburg resilience translated directly into managing screaming fans and complex logistics during the 1963 UK tours.

The Evolution of The Beatles

I trace their evolution through the Hamburg residencies (Aug 1960-Dec 1961, plus 1962), where marathon gigs at the Indra, Kaiserkeller, Top Ten Club and Star-Club-sometimes up to eight hours nightly-forced tight arrangements and a broadened repertoire. You can hear the change on Star-Club tapes and early demos; I cite the Top Ten Club run (Apr-Dec 1961) as pivotal. For background read Why did the early Beatles play in Hamburg? Was there a …

Musical Growth

The relentless Hamburg schedule taught me how repetition sharpens craft: up to eight-hour nights had them perfecting solos, tightening vocal harmonies and expanding setlists to dozens of numbers. You can point to early originals like “Love Me Do” (1962) and clearer Lennon-McCartney interplay as direct outcomes, while exposure to American R&B and demanding German audiences pushed more adventurous arrangements that later helped in the studio.

Band Chemistry

Living and working in Hamburg welded the group: I saw how shared long days, cramped lodgings and onstage pressure made roles clearer-John’s edge, Paul’s melodic bass, George’s lead lines and Pete Best’s steady backbeat-so you could feel a unit rather than four individuals. The constant gigging created unspoken cues and tightened timing important for later studio precision.

After Hamburg I noted interpersonal shifts: the grind produced sharper arrangements but also fractures-Pete Best remained their drummer through most Hamburg periods and was replaced in August 1962, which changed dynamics. You can trace how that personnel swap and years of shared pressure accelerated decision-making, tighter harmonies and the professional discipline that made their Liverpool performances and demo tapes far more compelling to managers and labels.

Key Figures in Hamburg

I’ve mapped key figures from Allan Williams and Bruno Koschmider to Manfred Weissleder, and you can read a detailed timeline in A milestone in pop music – The Beatles in Hamburg. I note Horst Fascher’s role at the Kaiserkeller and Weissleder’s Star-Club promotions-both secured marathon residencies (often up to eight hours a night, six or seven nights weekly) that hardened the Beatles’ live craft.

Promoters and Club Owners

I single out Allan Williams, who arranged the initial 1960 Hamburg trip, and Bruno Koschmider, proprietor of the Indra and Kaiserkeller, whose pay and schedules forced long sets. Manfred Weissleder later founded the Star-Club in 1962 and relied on Horst Fascher as bouncer/MC. I emphasize that these owners booked weeks-long residencies, so the Beatles accumulated hundreds of hours onstage within two years.

Rival Bands

I focus on Rory Storm and the Hurricanes, Tony Sheridan’s Beat Brothers, and other Mersey acts that rotated through Hamburg; competition for top billing at the Kaiserkeller and Star-Club made the Beatles expand repertoire and tighten arrangements. You saw direct pressure to outplay peers nightly, which accelerated their move from covers to distinctive originals and tighter three-part harmonies.

Rory Storm’s flamboyance and Ringo’s presence pulled audiences, prompting the Beatles to lengthen sets to as many as eight hours and to add five to ten cover numbers each night. I point to the June 1961 Tony Sheridan sessions in Hamburg-where the Beatles backed him on “My Bonnie”-as a practical studio template that showed them how to work under session constraints and raised their local profile.

Impact on Songwriting

You can trace the shift in their songwriting directly to those Hamburg stretches (1960-62). Playing up to eight-hour sets at Indra, Kaiserkeller, Top Ten and Star-Club forced John and Paul to tighten hooks, compress verses and sharpen choruses; I hear that editing in songs like “Please Please Me” and “I Saw Her Standing There.” Seven nights a week road-testing material accelerated their move from covers toward concise originals that worked live.

Original Compositions

They began writing originals to survive long club marathons and to stand out; I note Lennon-McCartney drafts were rehearsed nightly and rewritten after each crowd reaction. By late 1962 they had a stack of originals road‑proofed for studio work, with melodies pared down, vocal dynamics sharpened and lyrics tightened to fit 2-3 minute singles that could ignite a Hamburg audience within the first 30 seconds.

Covers and Influences

R&B, rockabilly and early Motown records provided a living textbook: Chuck Berry’s storytelling, Little Richard’s shout-singing and Carl Perkins’ phrasing shaped their approach. I watched how your favorite Beatles tracks absorbed rhythmic accents, guitar licks and call-and-response from covers they performed nightly, turning borrowed elements into a language they could use in original songs.

For example, I can point to their versions of “Twist and Shout” (Isley Brothers), “Long Tall Sally” (Little Richard), “Roll Over Beethoven” (Chuck Berry) and later “Money” (Barrett Strong) – each taught them vocal grit, stop‑start dynamics and the art of a single hook. Nightly repetition turned those elements into instinct: you hear the exact shout patterns and stop-time breaks reappearing in early originals and studio takes.

The Return to England

I noticed they came back to Liverpool in 1961-62 leaner, louder and far more disciplined after months in Hamburg; your typical Cavern Club show now featured tighter harmonies, economy in solos and stage routines learned under nightly pressure. The Polydor session for “My Bonnie” (June 1961) raised their profile, and that single indirectly led Brian Epstein to see them at the Cavern Club in November 1961, setting the next phase of their career into motion.

Preparing for Fame

They built stamina with marathon shifts-sets running four to eight hours, six nights a week-so I can point to the way they expanded repertoire from a few dozen to dozens more covers and early originals, including Chuck Berry, Little Richard and Motown material. You see how that volume forced concise arrangements, sharper timing and audience-reading skills that made their later studio work economical and radio-ready.

Lasting Impressions from Hamburg

I trace several lasting effects to those clubs: raw stagecraft, a tougher sonic edge and a repertoire-swelling that fed Lennon-McCartney songwriting. The live pressure honed call-and-response vocals and staccato choruses you hear on singles like “She Loves You,” while the Polydor recordings from Hamburg gave them a tangible demo that helped attract managerial interest.

Specifically, residencies at the Indra, Kaiserkeller, Top Ten Club and Star-Club between 1960-62 meant hundreds of nights and sets sometimes totaling up to eight hours; I find that this relentless repetition tightened their harmonies, taught economical soloing and pushed Paul toward melodic bass lines that anchored later arrangements, all of which you can trace through their transition from club band to chart-topping act.

Conclusion

On the whole I believe the long, relentless nights in Hamburg forged The Beatles’ musicianship, stamina, and repertoire; those marathon sets taught me-and you-how to read a crowd, tighten arrangements, and adapt to shifting lineups and audiences, shaping your expectations of live rock. The experience hardened their work ethic, broadened influences, and made their stage craft unmistakable, so when you hear their later recordings you can hear the night-by-night discipline and confidence that grew from those gritty German clubs.

FAQ

Q: How did the intense playing schedule and rough audiences in Hamburg shape the Beatles’ musicianship?

A: The band played long nightly residencies with multiple two- to three-hour sets, forcing them to expand and tighten a large repertoire, improve tempo control, and develop endurance. Frequent exposure to hostile or demanding crowds taught them to project energy, sharpen stagecraft, and adapt arrangements on the fly. That daily repetition turned loose covers into tight, polished performances and built the technical foundation they needed for studio work and high-pressure shows.

Q: In what ways did Hamburg influence the Beatles’ image, lineup, and creative direction?

A: Hamburg thrust them into a multicultural, artistic scene where contacts like Astrid Kirchherr and Klaus Voormann affected their look and visual identity, helping popularize the mop‑top aesthetic and a more striking stage presence. The city also coincided with personnel shifts-Stuart Sutcliffe stayed for a time and then left, Pete Best drummed during the Hamburg years-which tightened the group dynamic and clarified musical roles. Playing a wide range of material night after night nudged them from skiffle toward rock, R&B, and more nuanced pop arrangements, laying groundwork for original songwriting.

Q: Did Hamburg actually lead to recording and career opportunities for the Beatles?

A: Yes. While in Hamburg they backed Tony Sheridan on commercial sessions, producing the first records that circulated beyond Liverpool and introduced their sound to a wider audience. Their reputation as a hardworking, professional live act attracted better bookings and paid for equipment and travel. The combination of recordings, press mentions, and return visits to Liverpool helped them catch the attention of industry figures and set the stage for their later management and recording breakthroughs.